About The Place Where Van Gogh Took His Own Life : A New Hypothesis

Warning: This hypothesis, based on verified historical documents, is solely the responsibility of its author.

– To Marianna Reiley Burt

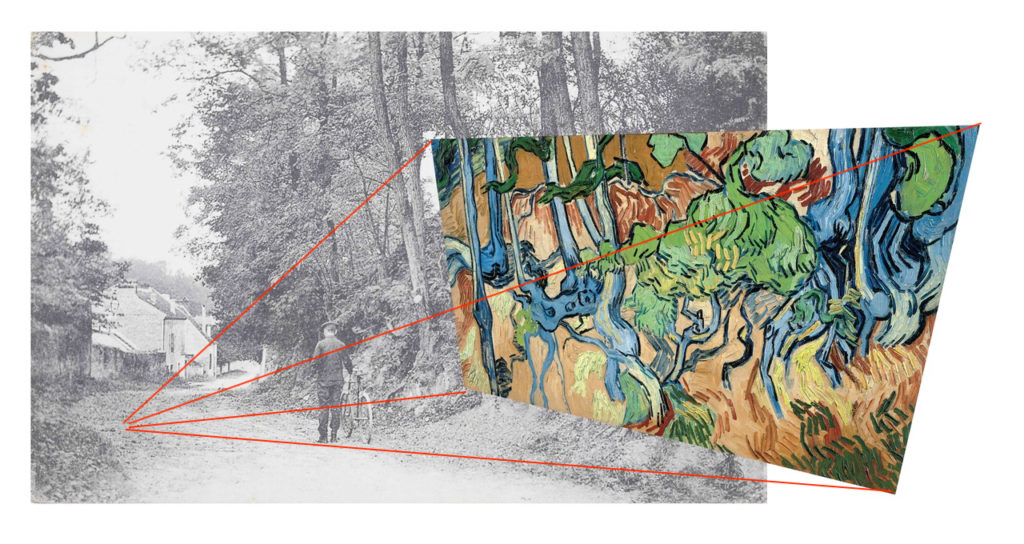

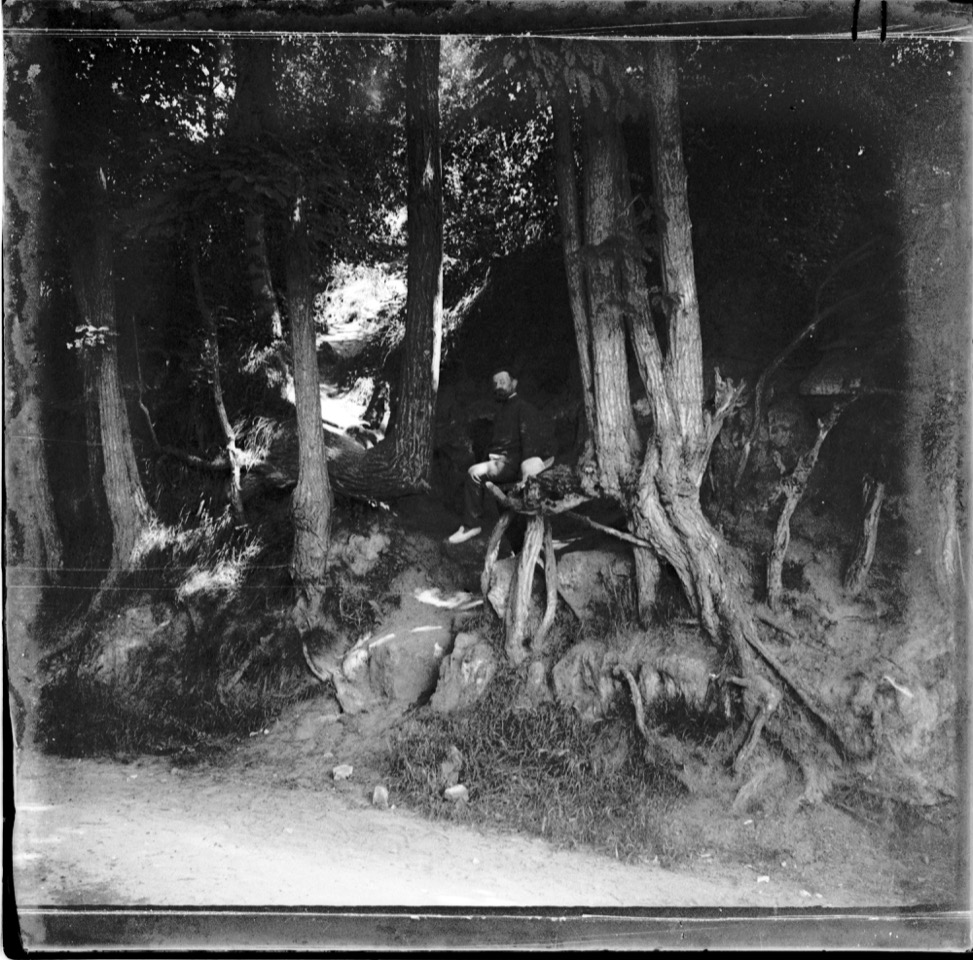

On July 27, 1890, Vincent van Gogh painted his last work: Tree Roots He spent a good portion of the day on it. The execution is calm and deliberate. The painting is not fully completed. In particular, a small root is curiously left unpainted. We can see its outline, but it remains raw canvas.

The interplay of shadow and light allows us to approximate the time of day when the last touches to the painting were applied: the sun’s rays strike the trunks and foliage on their left side, indicating it’s late afternoon or early evening.

The painting is atypical. It’s the only large-format composition that doesn’t seem to have any commercial intent. All the others are meant to be sold. This one is unsellable.

This final masterpiece is the culmination of a reflection on the struggle between life and death, a last testimony and a final message, with the primary recipient being the artist’s brother, Theo van Gogh, his best friend and financial supporter.

A Sword of Damocles: Syphilis

Van Gogh was well familiar with the subject before immortalizing it. Located about a hundred meters from the Café de la Mairie (Ravoux inn) where he had been staying since May 20, 1890, this hillside along the old Auvers road, overrun with spectacular-rooted black locust trees, had certainly not escaped his attention. On the plateau situated immediately above the hillside, Van Gogh painted around July 8th his famous Wheat Field with Crows, one of his last canvases, a haunting testament to a troubled state of mind he described in a letter to his brother Theo:

“Having returned here, I too felt deeply saddened and continued to sense the storm threatening you weighing on me as well. What can one do? You see, I usually try to remain in good spirits, but my own life is also attacked at the very root, my step too is faltering.”

To Theo and Jo, around July 10, 1890.

This passage, which links the storm from Wheat Field With Crows to “Tree Roots”, highlights Vincent’s main concern at this particular point in his life: the threat of syphilis. The symptoms were increasingly apparent in Theo, and the painter was convinced he was also infected.

Adolphe Tabarant, an art critic and journalist, documented this almost completely forgotten or overlooked fact in a review of Van Gogh’s biography by Théodore Duret, on page 4 of Paris Midi (March 8, 1917):

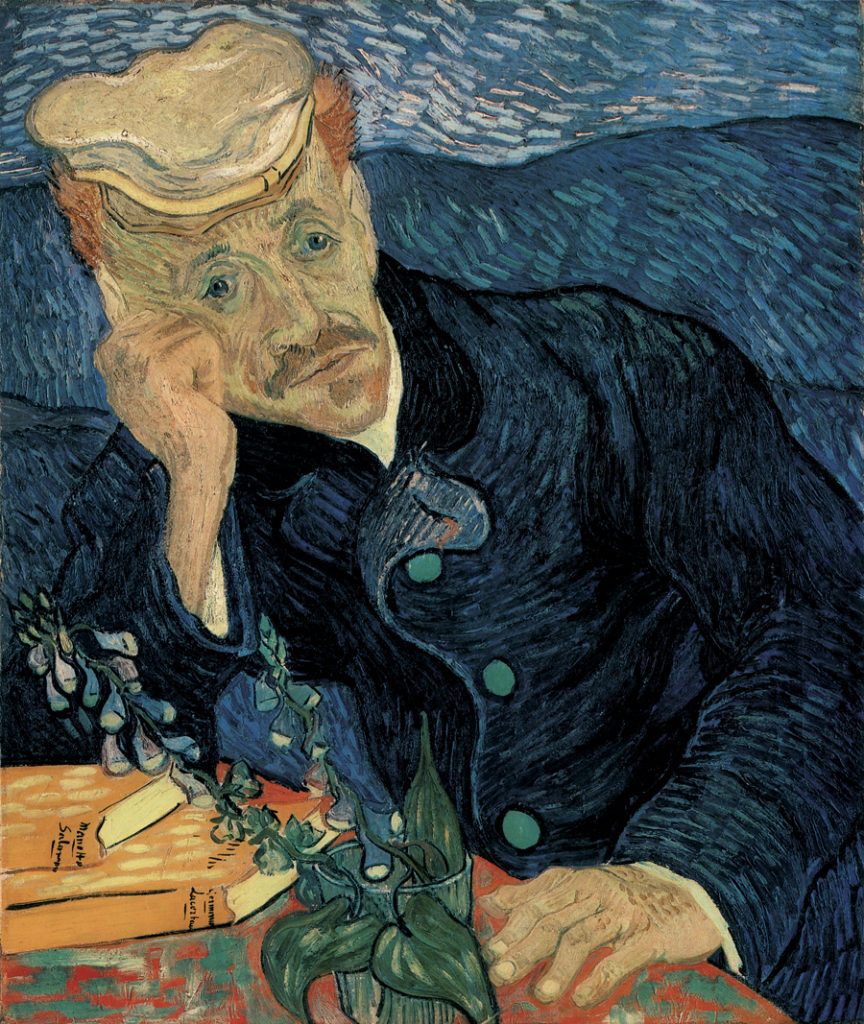

“Théodore Duret attributes this suicide to the anxiety caused by his cerebral condition, and at the same time, the sorrow of being a burden to his brother Theo. I would like to add that a phobia haunted him, that of the ‘scourge.’ He constantly questioned the excellent Dr. Gachet, his neighbor, about this terrifying ailment, who has recounted it to me numerous times. ‘I must have it, I have it,’ he whispered. And he painted relentlessly to escape the obsession. In truth, he was primarily tubercular.”

Tabarant knew Dr. Gachet very well and had also met Van Gogh during his Parisian period between 1886 and 1888. His account aligns with that of the doctor’s son, Paul Louis Gachet, who cites a note from his father in the manuscript of his posthumous book “The 70 Days of Van Gogh in Auvers”: “Unfounded syphilimania.” In other words, the doctor noted the painter’s obsession with having syphilis, also called the “scourge,” whose final stage is paralytic dementia. “Unfounded” perhaps because the symptoms that would indicate the disease were not evident.

To stop thinking about this threat, the artist had followed the doctor’s recommendations and threw himself into his work “full force,” meaning with all his energy. He had already experienced several terrifying episodes of psychosis and feared the next one, which might well be the one that would make him permanently lose his mind or lead him to a long and horrifying agony. What would he then leave for his sick brother? The work of a madman? For a painter who had spent 10 years learning his craft with inconceivable tenacity, total dedication, and unparalleled selflessness, this was an unbearable prospect.

His incessant activity, the extraordinary productivity of the last weeks of his life, had a dual purpose: the symptomatic treatment of the syphilimania diagnosed by Gachet, and a sense of urgency. He had to create as many paintings as possible, demonstrating the strength of his art and the relevance of his contribution before an inevitable end. His life was “attacked at the very root,” and his step was also faltering – meaning as shaky as that of his visibly sick brother Theo. Vincent felt the storm threatening both of them.

The deep conviction that the illness would prevail also provides an explanation for the fact that Vincent carried a revolver during his time in Auvers. It should be noted that the type of revolver history has recorded, a 7mm Lefaucheux, was extremely common in 1890, and its carrying was not regulated. There was no special effort to be made, no difficulty in acquiring one. A sadly unverifiable testimony from the gunsmith Leboeuf of Pontoise mentions this supposed acquisition of the revolver by Van Gogh. And a drawing from the painter’s sketchbook shows that he indeed visited this place. However, in the absence of other testimonies or documents, it seems difficult to fully embrace this anecdote. Regardless, by carrying the weapon with him, he had the opportunity at any moment to leave on his own terms, being the architect of his death as he had been of his life, and not as a victim of fatal circumstances. The legacy he would leave behind would be that of a tragic hero sacrificed to the sun, and not that of a madman with delusional works. Let’s also dismiss the unfounded and improbable theory of a Van Gogh who went off to commit suicide in a farmyard on Boucher street, behind a pile of manure, which relies solely on the testimony of the father of a woman interviewed in the 1950s. One could also claim that he was killed by Ravoux, or the village priest, but without evidence to support such a claim, it’s hard to consider it.

Possession of the revolver, the choice of the final subject, and the timing of the suicidal act, at the end of the day, amidst the harvest and the setting sun, align perfectly with Vincent’s mindset in July 1890. The last hope of regaining health by returning to the north was crushed by the bitter realization that the disease was taking over again – a realization exacerbated by the disappointment of seeing that Theo, the last lifeline he clung to, chose to spend his vacation in the Netherlands, even though Vincent had done everything to have him come to Auvers with his family. Add to this a dispute with Dr. Gachet over the trivial matter of a delay in framing a work, and the conditions are set for the artist to feel alone, with a sense of abandonment, facing another mental breakdown. The draft of his last letter, dated around July 23rd, just four days before the tragic act, makes this abundantly clear.

“But still, my dear brother, there is this that I have always told you, and I say it to you again with all the seriousness that can come from thought diligently focused on striving to do as well as one can… this is what I can tell you at a time of relative crisis…”

According to his indisputable testimony, on July 23, Vincent had difficulty concentrating and was facing a crisis. He thus confirmed Theo’s fears, who also sensed the onset of this new episode.

The Scene of the Tragedy

The mindset, the weapon, and the specific circumstances tragically converge to explain Van Gogh’s suicidal act. However, there remains an incomprehensible element in the sequence of events as we have received it: the location chosen by history, “behind the castle,” which does not seem consistent with the calculated and deliberate manner in which Van Gogh ended his days.

According to Paul Louis Gachet, who was 17 years old at the time, towards the end of the day on Sunday, July 27th, Van Gogh would have gone about a kilometer from the Ravoux inn: “in the fields behind the castle [château].” In 1904, the doctor’s son, having become a painter himself, even produced a small oil painting of the said location, which he believed to be near the Chemin des Berthelées. In the painting, one can see the enclosing wall of the Château de Léry park on the right, hay bales on the left, and a thatched-roof farmhouse set against a landscape that stretches out onto the neighboring plateau to the east. It was indeed necessary to move the supposed location to this point to reconcile the two parts of the statement “fields behind the château,” as there were no fields (and still are none) behind the château, only a vast tree-filled park.

Corroborating the account of Gachet’s son, Émile Bernard, Vincent’s friend present at his funeral, provided the first written account of the painter’s death in a letter dated July 31, 1890, addressed to his friend Albert Aurier:

“On Sunday evening, he went into the Auvers countryside, laid his easel against a haystack, and went to shoot himself with a revolver behind the château. Under the force of the impact (the bullet had passed below the heart), he fell, but he got up, and consecutively three times, to return to the inn where he stayed (Ravoux, town hall square) without mentioning his injury to anyone.”

This account blends confirmed facts with unverifiable — and quite surprising — elements. Nothing suggests that Vincent placed his easel against a haystack, and nothing can confirm that he rose up three times. It’s unlikely he took his easel with him: his last painting, “Tree Roots”, was at Ravoux’s. As for the Christ-like imagery of the condemned rising three times… Émile Bernard, in any case, didn’t get this information firsthand as he arrived in Auvers after his friend’s death. He even mentions that he’s relying on reported events.

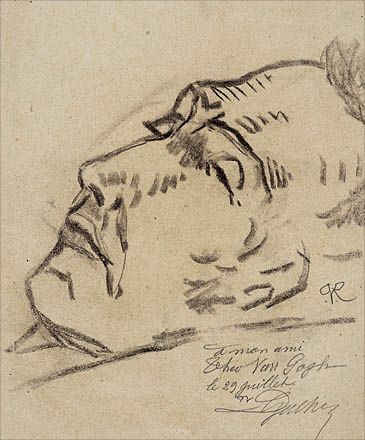

“… his suicide was absolutely calculated and desired with full clarity. A rather characteristic fact that was reported to me about his desire to disappear is this: ‘It’s to be done again then,’ when Dr. Gachet told him he still hoped to save him.”

The most reliable source to know the location of the drama and the intentions of the unfortunate is naturally Vincent himself. On his deathbed, he was able to inform Theo, Dr. Gachet, Dr. Mazery, Anthon Hirschig, the police, and the Ravoux family about the exact location. Yet, the precision of the location may seem trivial – after all, what difference could it make at this stage? But since the revolver did not return with its owner, in a village where children played, finding the murderous weapon naturally mattered.

Adeline Ravoux, 12 years old in July 1890, stated in a 1953 radio interview that her father and Theo went in search of the weapon, without success. Her remarks on this subject are imprecise. The interviewer puts words in her mouth: “Yes, it was said that it was behind the château, where they were.” And Adeline reacts: “Yes, it was around those parts.”

The three testimonies serving as the basis for the idea that Van Gogh went “behind the château”, more than a kilometer from the inn to shoot himself in the chest, are as follows: the indirect testimony of Émile Bernard, who did not know Auvers-sur-Oise; the late testimony, conveyed by a painting, 14 years after the fact, by Paul Louis Gachet, whose remembrances of Van Gogh were accompanied by inaccuracies and contradictions; and finally that of Adeline Ravoux, 12 years old in 1890, from whom a vague confirmation is extracted, indicating above all that she doesn’t know much about it.

The mention “behind the château”, whose distance from the site of Van Gogh’s last painting and the Ravoux inn defies common sense, is, however, too precise to be an invention. In the equation of the suicide, can this mention be explained in any other way than by a distant and haphazard wandering?

After extensive research, twists and turns, challenges, and the indispensable help of several people who were let in on the hypothesis presented in these lines, it appears that the coherence of this tragic day indeed extends to the scene of the drama, and is not left to chance. The choice of this location is, on the contrary, the culmination of a thought process conducted in full lucidity.

Vincent had announced it in a letter to Theo, in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, at the beginning of September 1889:

“The work is going quite well – I am wrestling with a canvas I started a few days before my indisposition. A reaper, the study is all yellow, extremely thickly painted, but the motif was beautiful and simple. I then saw in this reaper – a vague figure battling like a devil in the full heat to finish his work – I then saw the image of death, in the sense that humanity would be the wheat being reaped. So, if you will, it’s the opposite of the sower I had tried before. But in this death, there is nothing sad, it takes place in full light with a sun that floods everything with a fine golden light.”

In light of this meaningful passage, it’s unsurprising that Vincent chose to die in a wheat field, at harvest time, under the setting sun. What is surprising, however, is that he would have walked more than a kilometer to get there, when the same conditions were met just a hundred meters from where he painted his last canvas – which represents more than just a set of roots on the roadside. It also depicts, as shown in a photo of the place taken around 1906, the steep path that leads to the plateau located right above: the plateau “behind the church”, east of the one that is “behind the château”, and where stretch the fields where he painted the Wheat Field with Crows.

Three Châteaux for One

But how can we reconcile this more plausible location with the mention of “behind the château”? One explanation might be that there was another château in Auvers-sur-Oise in 1890, bordering the plateau “behind the church”, and that both Paul Louis Gachet and Émile Bernard misunderstood which château was being referred to.

Indeed, in 1890, there were even two châteaux that could explain this possible confusion. The first one is pointed out by Samson Cazier on the map he drew of Auvers in 1899. It refers to a medieval castle attached to the church, which had lost its distinctive appearance. The towers had been knocked down. Only a main building, the bases of two towers, and some walls remained. However, Cazier’s mention attests to the fact that the term “château” was still in use, and clearly, this place was noteworthy. Relative to the village, it is behind this château that Van Gogh painted his Wheat Field with Crows, and it seems coherent that this is the place Van Gogh had chosen to end his days. Moreover, this is what Vincente Minnelli envisioned in his film Lust for Life, shot in 1954. That year, he could rely on the stories circulating in the village, which clearly pointed to this location – or at least this plateau. Two sources support this hypothesis: first, the investigative work of Mark Edo Tralbaut, a specialist and biographer of Van Gogh, who claims in Vincent van Gogh, The Misunderstood to have collected what he called “popular tradition”, pointing to the plateau beyond the church (and thus the ruins of the medieval castle also located there). Then there is an undistributed interview from 1953, kept in the INA archives, with a member of the village’s town council, a former employee of art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who had deep knowledge on the subject and leaves little room for doubt.

“Are there people here who remember that Van Gogh committed suicide?”

“Yes, yes, yes, we even know… the mayor, when I asked him, told me ‘he committed suicide here, just a little further, a few hundred meters from the cemetery, maybe three to four hundred meters, out in the open field over there.'”

The interview wasn’t filmed, so we don’t see in which direction the interviewee is pointing, but the approximate distance given matches the gap between the cemetery and the plot located just above the place where Van Gogh painted his last painting, leading to the path that crosses the Tree Roots site. This striking and moving interview, which lets us dive into the early 20th century alongside Utrillo, Picasso, Vollard, Van Dongen, and the Berlin merchant Paul Cassirer, was generously brought to my attention by Patrick Glâtre.

The second château that could explain the mistake is even more interesting than the ruins that were adjacent to the church, which are beautifully restored today. In fact, the building that today houses the Daubigny Museum, located on Rue de la Sansonne and known as the “Manoir des Colombières”, was called the “Château des Colombières” in 1890. This is confirmed by numerous references in documents from that period, both in scholarly writings and in the press. For example, the historian Henri Mataigne wrote in 1901:

“The Château des Colombières now belongs to Mr. Joseph Depoin. On Daubigny Street, one of the main entrances to this castle features a crenellated door with niches that artists have often sketched.”

Its domain stretched for hundreds of meters and included a very beautiful garden. The Vavasseur school was built on its former lands. On the map above, it is surrounded in green.

However, on the scale of Auvers-sur-Oise, which extends over more than eight kilometers, “the château” obviously referred to the Château de Léry, which dominated the village. But for the Ravoux family, on a day-to-day basis, “the château” could just as easily refer to the Château des Colombières, of which they were neighbors.

The Château des Colombières was, and still is, located precisely between the Ravoux inn and the place where Vincent painted “Tree Roots”. Within the Ravoux household and inn, when asked where the painter had spent his last day, the natural answer was: “behind the château”. Even better, he had set up his easel just a few meters away from its enclosing wall. Likewise, the path passing between these roots, and the fields to which it led, were just as naturally located “behind the château”.

Murer’s Account

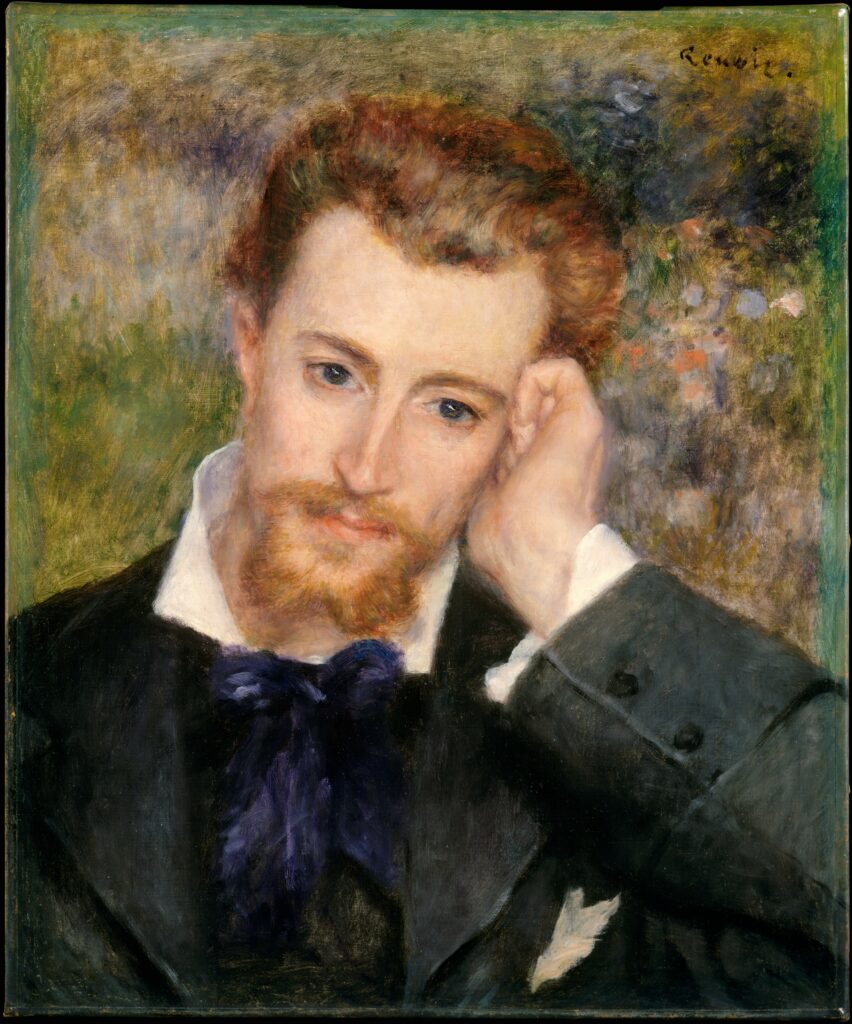

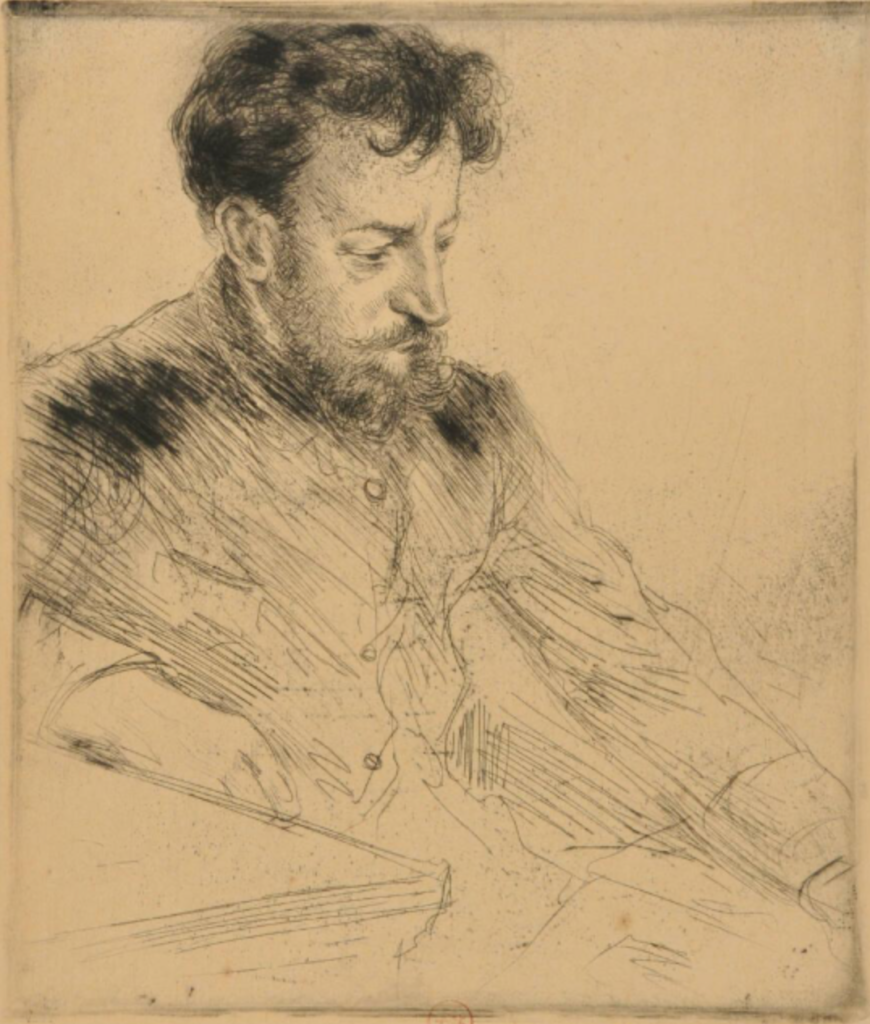

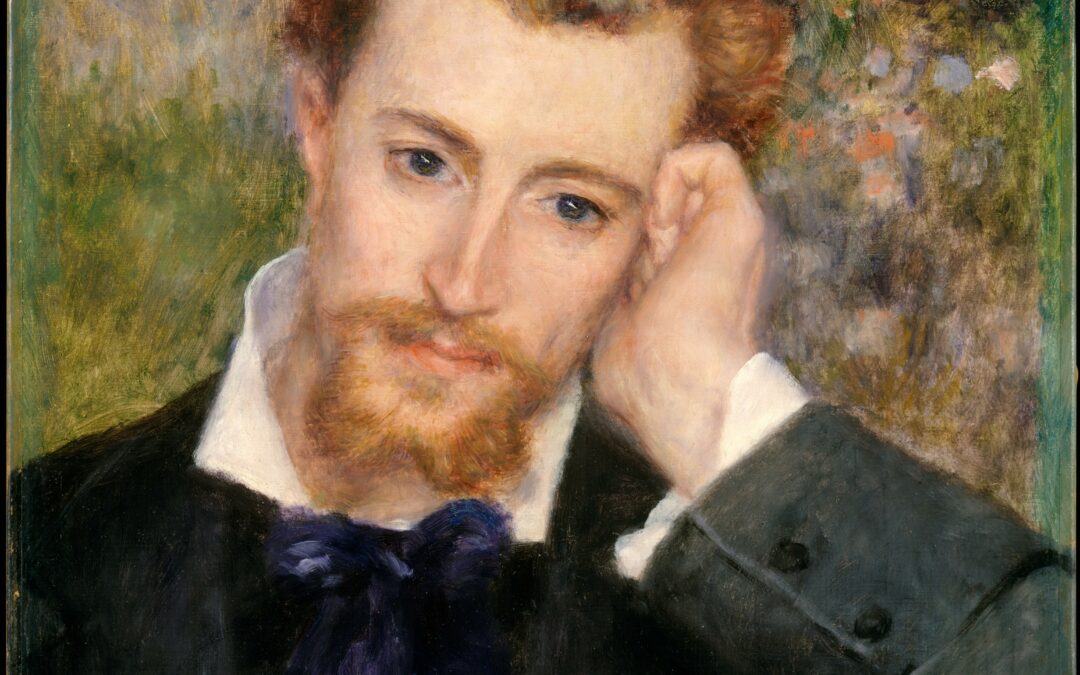

A precious testimony, whose story is as beautiful as it is tragic, came to support the hypothesis of this location for Van Gogh’s suicidal act. This testimony was delivered in 1975 in the December issue of the L’Œil magazine, in a detailed, high-quality article by Marianna Reiley Burt: ‘Le pâtissier Murer, a friend of the Impressionists’. The subject of this dense and effective contribution is Eugène Murer. This self-made man, selfless, generous, talented, intelligent, and sensitive paid a high price for his entrepreneurial success, hard-won from a modest social position. He had built a beautiful villa in Auvers, inspired by the approach of his friend Paul Gachet. In a specially designed outbuilding, he housed a fabulous collection of Impressionist paintings. Renoir, Monet, Degas, Guillaumin, Cézanne, Pissarro, Sisley, Vignon… The writer Paul Alexis, who will inventory them in 1887, mentions about 122 exceptional pieces that today would suffice to fill an internationally renowned museum. It seems unthinkable that Van Gogh did not seek to learn more in 1890, just as it seems unthinkable that Murer, knowing that Van Gogh was staying in the village, did not seek to meet him.

The fact that Van Gogh did not seek out Murer may have several reasons, the primary and clearest one being that he was firmly committed to dedicating his time to painting, rather than engaging in a social life for which he felt ill-equipped.

“If I work, the people here will come to my place just as easily without me going to see them on purpose than if I took steps to make acquaintances. It is through working that one meets, and this is the best way.”

To Theo & Jo, Auvers-sur-Oise, May 21, 1890.

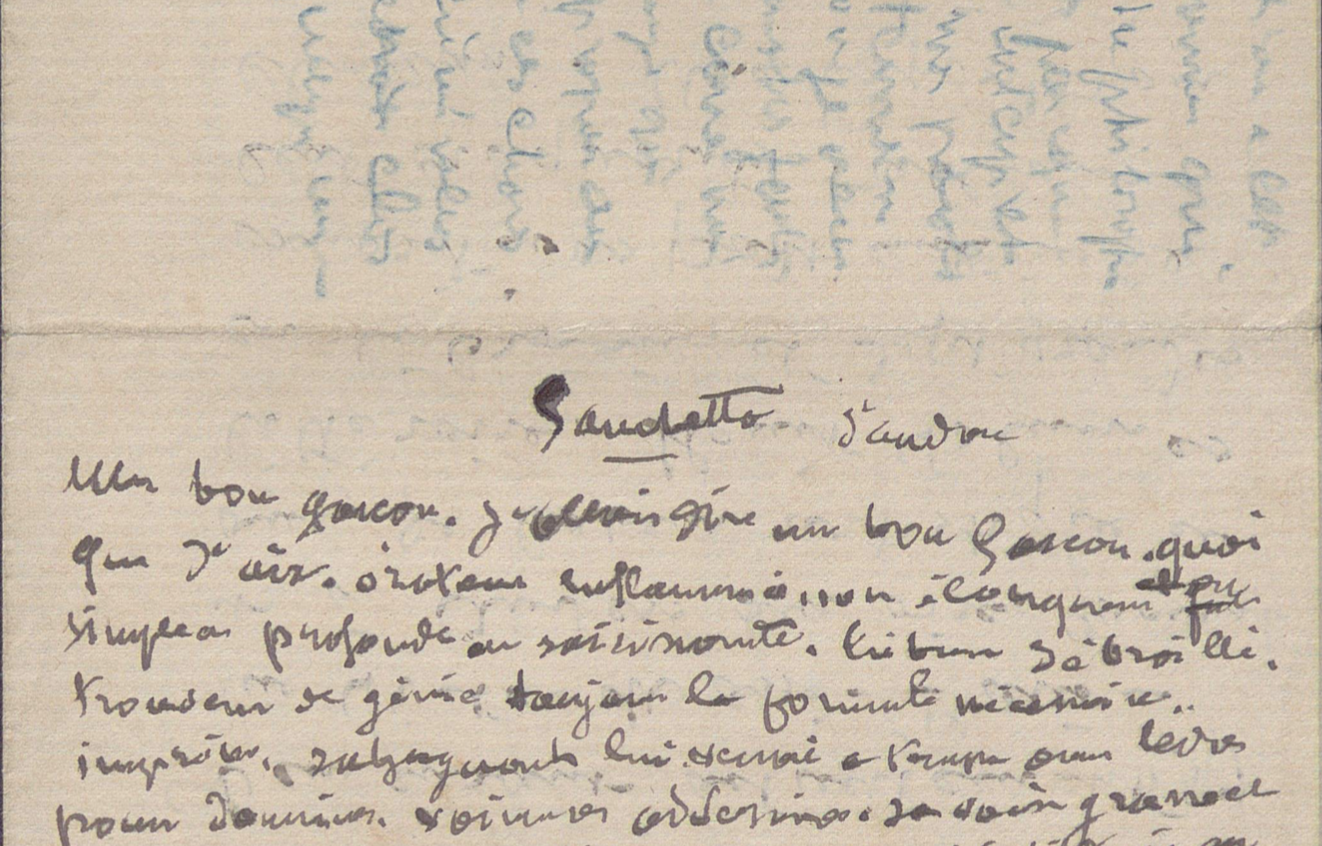

As for Murer not seeking out Van Gogh, as has always been assumed, this is contradicted by a testimony from Murer himself. Indeed, Marianne Reiley Burt, in her December 1975 article, cites two highly credible passages she extracted from Murer’s autograph notebook, who was also a writer, painter, and a remarkable pastelist. These passages are not dated but were written before 1906, at a time when it would have been entirely uninteresting for Murer to invent an encounter that did not happen; he did not need this to boost his significance, being close to a large number of painters who were much more famous at that time. Moreover, the passages contain several details perfectly consistent with what is known of Van Gogh. Marianna Burt writes:

“In the spring of 1890, Van Gogh came to Auvers where he would spend the last months of his life under the supervision of Dr. Gachet. Murer met him from time to time, and one day as he was painting, he wrote in his notebook, Van Gogh criticized his work saying, ‘You’re thin,’ he told me bluntly. ‘And your painting is thin. It’s too dry. You’ll need to add more fat there.’ The observation was accurate.”

This anecdote aligns perfectly with Vincent’s forthright nature, who was not one to mince words. The vocabulary used is also plausible. The Dutchman believed that the colors of Impressionism would quickly fade, and he recommended using pure colors in thick layers and strokes to preserve their freshness.

The second passage, however, is even more startling and informs us of the location of the suicide attempt:

“The last time I saw him alive, he was coming back from working on the plateau behind the church. It was in July. Very pale, he was dragging himself painfully, leaning on his easel stick. He still managed to get to his inn, Place de la Mairie. On the threshold, the innkeeper said to him, laughing:

‘What’s wrong, Mr. Van Gogh, are you dead?’

‘It’s almost the same,’ replied the artist. ‘Go notify Dr. Gachet. I have a bullet in my belly.’

The doctor was a personal friend of Van Gogh. He rushed over and found that the artist had shot himself in the heart. The bullet, hitting a rib, had deviated, and then, by a short circuit, settled in the left groin. Nothing could be done. It was a matter of a short time before death.

‘How long?’ asked Van Gogh, calmly. ‘Forty-eight hours,’ replied Gachet, as stoic as his friend. ‘Alright. Give me my pipe.’

And Van Gogh, silent, lying on his back, began to smoke. For two days, the artist remained like that: without complaints, without words, constantly smoking pipes that the doctor would pack for him, sitting by his bed.

At times, under the intensely sharp pains of suffering, Van Gogh would cast a deep, questioning look at Gachet, which, tragically eloquent, seemed to say: ‘It’s taking so long!’ Gachet would answer with a handshake, where the compassionate magnetism of his beautiful philosopher’s soul responded: ‘Just a little patience. Death is near.’

His friends gave him an artist’s funeral: simple and without speeches. He now rests in the small cemetery of Auvers, not far from where he shot himself in the heart. His face is turned towards the rising sun, towards the light he loved so much and of which he was one of the most powerful interpreters.”

This narrative raises some questions. Firstly, we now assume that Van Gogh returned to the Ravoux inn with his last painting before heading to the fields, carrying only his revolver. Thus, he wouldn’t have taken his “easel cane” with him. But this detail is less significant than the total absence, in this story, of Theo, Vincent’s brother, who indeed rushed to his side.

Clearly, Murer did not personally witness the agony of his unfortunate colleague. However, the details he provides are very accurate and corroborated by other testimonies: the desire to end it all, Doctor Gachet packing his pipe, the stoic resistance to pain, the trajectory of the bullet, and the burial. These details are thus obtained second-hand.

However, Murer and Gachet shared not only a common interest and commitment to Impressionism but also had excellent relations that extended to their respective families. At Murer’s funeral in 1906, there were only two attendees: the painter Goeneutte and Doctor Gachet. It is highly likely that the details about Vincent’s suicide and death in Murer’s text came from the doctor. Whether the pastellist truly saw Van Gogh himself descend from the plateau behind the church remains uncertain, but appropriating a testimony does not mean that the described events are false.

The most relevant element to relocate the place of Van Gogh’s suicidal act is the first sentence of Murer’s text: “The last time I saw him alive, he was returning from working on the plateau behind the church.” This same plateau is located “behind” the château adjacent to the church, and “behind” the château des Colombières.

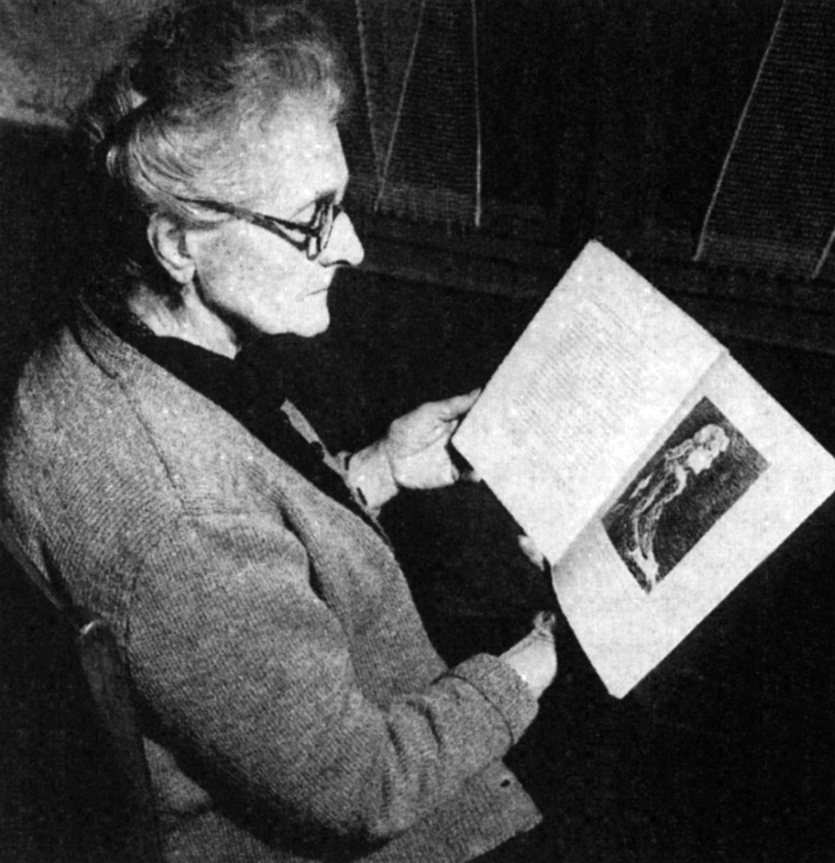

Marianna Reiley Burt’s article has been cited in one study or another, but has never been taken with the seriousness and attention it deserves. In the context of research on the new location of the suicidal act, during the preparation of the exhibition catalog for “Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise, the final months,” in 2022, even with the support of the Van Gogh Museum, I couldn’t locate Mrs. Burt, nor the valuable source she mentions. Other contributions by the same author could have given more or less credit to the document she presents, of which a footnote indicates it is in her personal possession. I only managed to deduce, from a single other document, that Mrs. Burt was a student of John Rewald, a great specialist in Impressionist painting.

Finding Marianna Burt

In the heart of the summer of 2023, during a conversation with reporter Michael Forsythe from The New York Times, I broached the subject of the curious disappearance of Marianna Burt, the elusive holder of a treasure that could provide a crucial argument for my research. Forty-eight hours later, Michael Forsythe had found all the contact information I needed to reach the art historian, which I did without delay.

Beyond the emotion that our subsequent exchange evoked in me, with a lady of advanced age but perfect intellectual sharpness, the story of the journey of Murer’s notebook convinced me that the trail I was on was the right one.

The notebook in question, which is of the same model as those kept at the Wildenstein-Plattner Institute, was given by Lucienne Tabarant to Marianna Burt in 1973, when she was a doctoral student under the supervision of John Rewald and was preparing a thesis on Paul Gachet. Lucienne Tabarant was the daughter of Adolphe Tabarant, an art critic and journalist, personal friend of Paul Gachet and Eugène Murer, who had also briefly known Van Gogh. Tabarant had even written the introduction to an exhibition catalog of Murer’s works. Thus, the provenance of the notebook is perfectly credible, and its journey has complete consistency. Unfortunately, Mrs. Burt informed me of a tragic event that led to the loss of the document and her research on Dr. Gachet. Everything, except for an engraving at a framer’s, was lost in the fire that consumed her house. The partial transcription published in L’Œil is all that remains today. This traumatic experience ended the promising early career of Marianna Burt, who then fully devoted herself to her other passion: law. She became a lawyer and is still practicing as these lines are written.

Conclusion

Considering all these elements, it seems entirely plausible that during the emotionally charged and trying days at the end of July 1890 at the Ravoux inn, the phrase “behind the château” might have led Émile Bernard and Paul Louis Gachet astray. For Émile Bernard, it was the only château he knew of. For Paul Louis Gachet, “the château” would naturally refer to the one he was most familiar with. In reality, the site of the suicide was indeed “behind” a château. But it wasn’t the Léry one.

This new hypothesis, which confirms popular belief, cannot claim to establish a new truth. However, the various sources presented above seem to me to suggest at least the possibility, if not the strong likelihood, that Van Gogh’s final steps were dictated by a clarity and determination of which he himself bore witness to his brother Theo, to Dr. Gachet, to the police who came to investigate the circumstances of his death, and finally to the Ravoux family. Instead of wandering more than a kilometer from his inn, driven by randomness and despair, Vincent went straight to the nearest wheat field, crossing the roots he had just immortalized, to confront, one last time, the sun amid the harvest.

It seems much more likely to me that the painter chose to die by sacrificing himself for the benefit of his brother and his nephew, in full light, in the image of a warrior preferring death to the dishonor of defeat. In this perspective, consistent with everything I have been fortunate enough to learn about the life, work, and thoughts of Van Gogh, I believe we should dismiss the thesis of the young Paul Louis Gachet, so curiously transcribed in his strange painting of an empty and improbable place.

Lastly, I warmly thank L’Œil magazine for agreeing to exclusively publish this hypothesis in its pages, thus paying tribute to the remarkable work of Marianna Reiley Burt, whose contribution to art history has thus experienced a strange, but wonderful fate.

——————————————–

———————–

———–

—–

Some questions and answers that form the structure of my investigation, before the decisive contribution of the interview with the municipal councilor of Auvers in 1953 and my contact with Marianna Reiley Burt.

- Do we know for sure where the suicide attempt took place?

No.

- Why ?

Because the only explicit and precise source for identifying this place is Paul Louis Gachet, who often blends autofiction and reality.

- Are there other testimonies?

Yes.

- What do they say?

Rue Boucher, in a farmyard behind a dung heap; The fields behind the church, near the cemetery; “in the fields”; “in the countryside”.

- Are these testimonies credible?

For some, more so than Paul Louis Gachet’s account.

- What is the primary source of information about the suicide location?

Van Gogh himself, but we don’t know exactly what he said. His indications were vague enough that the revolver was never found.

- What do different versions have in common?

None. The recurring elements are: “the fields” & “behind the château”.

- Were there multiple fields and/or châteaux in Auvers?

Yes.

- Which ones?

Two plateaus covered with fields are located “behind” châteaux. That of Léry and that of Colombières & the church (to which a château was attached).

- Can we exclude one of these two plateaus for any reason?

No.

- Can we establish a hierarchy in the likelihood that it’s one place over the other?

Yes. The plateau behind the Colombières castle is closer to the Ravoux inn, and is just above the location where Van Gogh painted “Tree Roots,” his last painting. However, Émile Bernard’s testimony, which refers to “the château” as if there were only one, seems to designate the most visible of Auvers’ châteaux: that of Léry. In a letter, Van Gogh himself identifies the Léry château as “the château”, also as if there was only one.

- Did Émile Bernard know the Château des Colombières?

Impossible to confirm or deny. It is likely that he only knew Auvers superficially.

- Did the funeral’s protagonists (Theo, Ravoux, Gachet, Hirschig) know what “the château” meant?

To varying degrees, with different landmarks.

Thanks Wouter for this comprehensive well thought out hypothesis, based on verified historical documents. It is something I had thought and believed and corresponded with you and others about during and after the pandemic. Here in this article you supply the necessary facts and proofs that do indeed seem to bring a moving reality to that sad time in Auvers of Vincent van Gogh’s great but short life. I am sure that there is more that you will bring to light in the future and that you will contribute to Vincent’s legacy. Well done and thanks again Kind Regards Alan Trussell

As you know I have posted elsewhere my thoughts around Vincent’s last painting – the tree roots. However I have also come across the following on page 137 in the 1934 book by Peter Burra (Great Lives) published by Duckworth WC 2. “on the evening of 27th July he climbed up BEHIND THE OLD CHATEAU AMONG THE TREES. – There was a last letter in his pocket,…….etc etc”.I wonder if this (BEHIND the OLD Chateau) notation is of any help in searching for the possible truth to Vincent’s very last last day and your hypothesis? Kind Regards Alan