On the evening of Sunday, July 27, 1890, in a wheat field above Auvers-sur-Oise, Vincent van Gogh shot himself in the chest with a revolver. He aims for the heart, but the bullet misses its target. Deflected by a rib, it completed its fatal trajectory in his intestines, avoiding any vital organs. Death not coming, the painter decides to return to the Ravoux Inn, also known as the Café de la Mairie.

Vincent managed to climb to his attic room and lie down on his bed. Arthur Ravoux took the artist’s initial account and called Dr. Mazery, a young doctor who had recently graduated and settled in the village. Ravoux also notified Dr. Gachet, a friend of the painter. Out fishing by the Oise River with his son, Gachet was not at home. It took time to locate him, time for him to find his medical kit, and even more time for him to journey from Rue des Vessenots to the inn. Meanwhile, Mazery treated Van Gogh’s wound, and upon being joined by his more experienced colleague, they realized there was nothing left to do but wait. Hope was scarce.

It took Van Gogh around thirty hours to die. His brother and best friend Theo was informed in time for a heartfelt farewell. On Tuesday, July 29, Vincent passed away around one in the morning. During the following day, with support from a few friends who came to share his grief and honor the memory of the painter, a heartbroken Theo organized the funeral. The large room at the Ravoux Inn served as a funeral parlor. The deceased was buried on Wednesday, July 30, in the Auvers-sur-Oise cemetery, surrounded by wheat fields during harvest time. Dr. Gachet delivered the eulogy.

Van Gogh’s death has fueled many fantasies. The most dramatic is the conspiracy theory posited by Steve Naifeh and Gregory Smith in their biography, which sparked controversy and left a lasting stain on Van Gogh’s memory: an audacious conjecture suggesting it was not suicide, but homicide.

Prior to the publication of Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Rise of the Artist by Martin Bailey (Frances Lincoln Publishers Ltd, 2021), it was established that the first newspaper to report Van Gogh’s death was L’Avenir de Pontoise, in a few lines, on August 3. A great tragedy had struck one of the greatest artists the world had ever known, and the media attention given to his death seemed to be limited to a few lines that treated the case like any other news item in a regional newspaper with a small circulation.

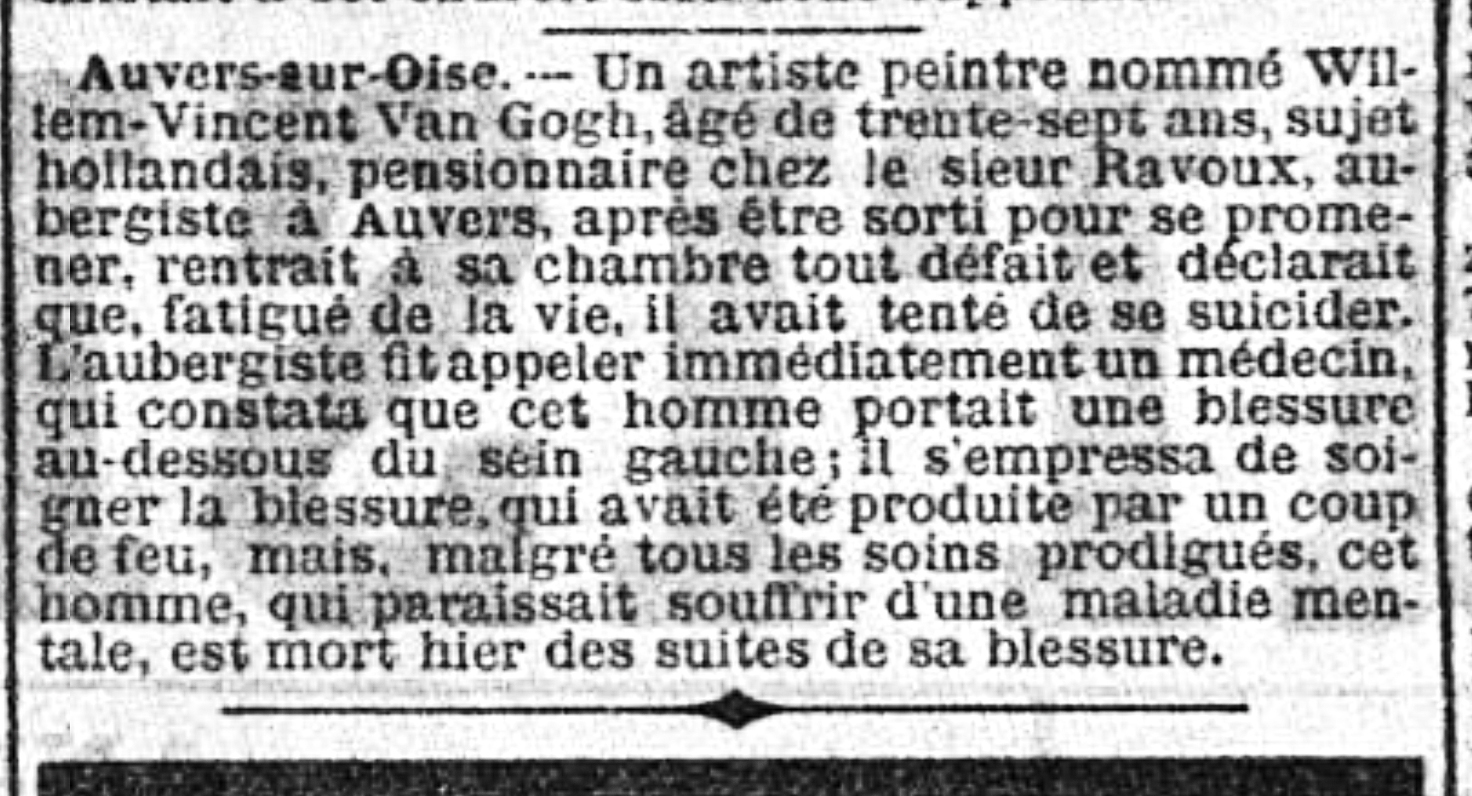

Now, on page 139 of his book, Bailey reproduces an entry from the Petit Parisien dated August 2, 1890, which also brings the sad news, on the last page of the newspaper. I had read Van Gogh’s Finale with great attention in 2021, but I did not realize at the time that this publication was rich in meaning, and brought interesting nuances. The text is a little longer than the one in L’Avenir de Pontoise, and particularly moving:

“A painter named Willem-Vincent Van Gogh, 37 years old, a Dutch national, staying at Mr. Ravoux’s inn in Auvers, returned to his room exhausted after a walk and declared that, weary of life, he had attempted suicide. The innkeeper immediately summoned a doctor, who discovered a wound below the man’s left breast; the doctor tended to the gunshot wound, but despite all the care provided, the man, who appeared to suffer from a mental illness, died yesterday from his injury.”

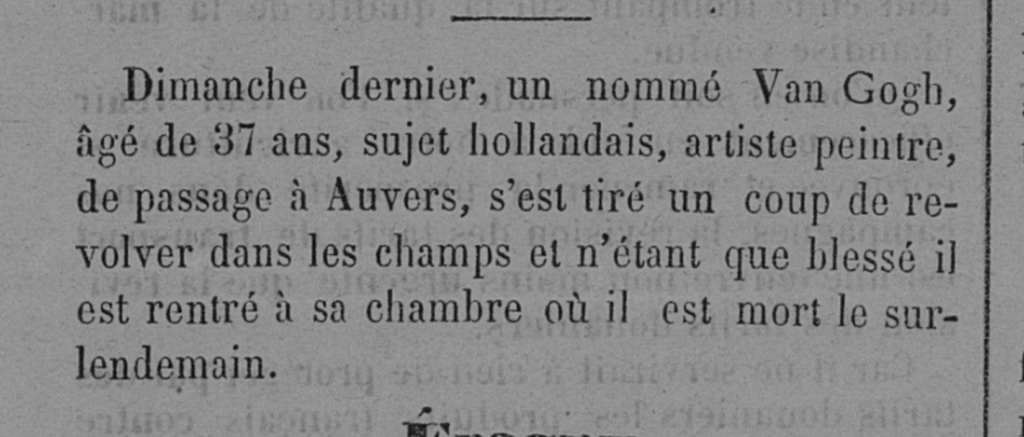

The following day, this text was reproduced almost verbatim in Le Moniteur universel. The last sentence was altered: “…but, despite everything, Willem, who appeared to suffer from a mental illness, did not take long to succumb.”

Beyond the emotion of reading an account so close to the events, several innocent-looking elements contain valuable insights.

The first information is related to the nature of this brief news item, published in a Parisian newspaper. If the news traveled so quickly to Paris, it’s because a journalist considered this particular suicide interesting enough to report it in the capital. At the same time, the article confirms that Van Gogh was an unknown painter to the general public: he is referred to by his middle name, even though he signed his paintings “Vincent.”

The second piece of information is found at the end of the article: “died yesterday” means that the article, if accurate, was written on Wednesday, July 30, the day of the funeral. It’s hard to be closer to the events, which lends credibility to its content, especially to the third and last interesting piece of information revealed by these few lines.

The mention of “going out for a walk,” likely obtained from direct witnesses, contrasts with what is known about Van Gogh’s habits. When he ventured out, it was with a specific goal in mind (typically to paint) rather than simply to take a stroll. This information probably originated from Ravoux, who saw him leave the inn—clearly unaware of his boarder’s intentions. Conspiracy theorists surrounding Van Gogh’s death consistently bring up the suspicious fact that the artist’s painting and materials were never found, which could imply that “someone” had removed evidence of a crime. However, this apparent disappearance can now be perfectly explained: there was nothing to conceal. Van Gogh had set out to end his life, and the only thing he needed for that purpose was his revolver.